by John M. Souders, July 2021

As we swelter through another hot summer, it’s hard to believe that a century or so ago Waterford successfully marketed itself as an idyllic refuge from the simmering cities. In the latter third of the 1800s, after the railroad pushed west into the Loudoun Valley, farms and villages competed eagerly for cash-paying customers fleeing the urban heat.

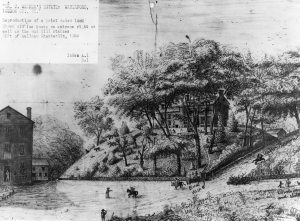

Jake Walker, advertising his comfortable home [Mill End—40090 First Street] overlooking Waterford’s mill, promised guests in 1895 “an Ideal Summer Home—an abundance of fruit, flowers, ice and shade; high and dry; no mosquitoes; two hours’ ride from Washington.” The previous year he had attracted “quite a number of Baltimoreans” for the season.

In 1874, from the other end of town [Huntley Farm—15578 High Street], fellow Quaker Charles Hollingsworth touted a “high situation and view of the mountains fine.” In the wake of the Civil War, money remained scarce, even in productive Loudoun, and summer boarders could help keep homeowners solvent. Still there were sometimes limits to their hospitality. For the Hollingsworths, “only a few persons without children can be accommodated.” In their defense, Huntley in those days was much less spacious than it became after Robert Walker’s modifications in the 1890s. But maybe they just didn’t need the extra hassle. Sally Bond, widow of Waterford’s longtime tanner, was blunter in 1886: “Small children refused.” For the older set she offered “plenty of space, ice, fruit [and] good table” at her place on Bond Street [Janney-Phillips House—40132]. The last named inducement would have been especially important at a time when Waterford had about as many dining options as it does today.

At the northeast edge of town [Moxley Hall—40266 Water Street], Lewis Shuey, who had married Sally Bond’s niece, added a couple of extra attractions to the usual list: “shutters, mountain air [and] daily mail,” the indispensable equivalent of today’s wifi. In 1874 Sally’s sister-in-law Rachel (Mrs. Samuel) Means [40128 Bond Street] advertised her place’s convenient access to Washington: “two trains daily.” (A few years earlier, Albert Brown had inaugurated a stage line between Waterford and the train station at Clarke’s Gap. He promised to “meet the 11 o’clock A.M. train daily. Passengers conveyed comfortably and safely. Fare either way fifty cents.”) Rachel was in dire straits at the time. Husband Sam had formed and led the pro-Union Loudoun Rangers in the war, and his former rebel antagonists were intent on driving him to financial ruin. When they succeeded, the Meanses moved to Washington where Rachel ran a boardinghouse to support the family.

If fine food, “good water” and mountain air did not restore soul, as well as body, there were summer camp meetings. These could be major affairs. One of the first was held in August 1871, exactly 150 years ago.

The Waterford Methodist Episcopal Camp Meeting will commence on Thursday, the 10th instant. Conveyances will be running daily to and from the depot. The railroad will pass all persons coming and going from the meeting at half fare.—The grounds are well shaded, and very conveniently located. The best accommodations will be provided for all who may come. Boarding and lodging of the best kind will be furnished for the entire meeting for $7, and boarding, exclusive of lodging, for $5. We are expecting a real, old-fashioned Methodist Camp Meeting, and most cordially invite all well-disposed persons to come.

Charles King, Pastor, Waterford, Loudoun co.

Three years later, unfortunately, attendees included persons not so much “well-disposed” as well-inebriated. A “Mr. Tavenner attacked a reverend, and the services were interrupted by a man under the influence of alcohol. The drunken man was quieted by the ‘brawny arm of a big father’ and then ‘subjected to painful effects produced by phrenological examination of the head by a fence rail.’” Quite a vivid image! and “but for the early stopping of the affray there would have been such a fight, as that there would not have been enough men on the ground to stop.”

“Jim Crow” was also in attendance. “At this same meeting a group of African-American women attempted to take advantage of their promised civil rights by seating themselves amongst a group of white women, but they were quickly removed from the meeting by a local officer . . . otherwise it is to be understood that good order was observed throughout and the meeting attended with many gratifying results.”

Not everyone emerged gratified from such gatherings, or even unscathed. Waterford historian John Divine recalled that “someone stuck a knife into” his grandfather Joe Divine—a staunch Methodist—at a camp meeting, though the injury was not serious.

The Baptists appear to have had better luck with their meetings. At a gathering in August 1881 held in Charlie Hollingsworth’s woods, the press reported “an immense crowd” in attendance each day, with “great numbers of vehicles” passing through Hamilton en route to the meeting.

For those seeking a tamer diversion from the summer heat, there were traveling entertainments like the medicine show that in June 1903 set up a tent for two weeks on the “colored school house lot” [Second Street School—15611 Second Street]. The operators had a sure-fire tactic to separate attendees from their hard-earned cash. “They offered a gold watch to the lady who would receive the most votes as being the most popular lady in town. The number of votes being regulated by the amount of medicine, &c. purchased, and when the final count was made on Monday night it was found that Miss Louise Fling, the accomplished daughter of our miller, Mr. W.H. Fling, had received a total of over 87,000 votes, and she was accordingly awarded the watch for being the most popular young lady in town. We congratulate Miss Louise (she was going on 14 at the time), and think she well deserves the compliment.” Political correctness had not been invented yet.