Excerpt from Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia: Chapter 21 – After Gettysburg, Chamberlin and Souders, 2011.

Late June [1863] found the Loudoun Rangers attached to a brigade assigned to protect the B&O tracks west of Baltimore, although as it turned out Stuart’s cavalrymen did minimal damage to that railroad as they hurried to Pennsylvania. On 25 June, when Lee’s intentions were still unknown, Army Chief of Staff Henry Halleck ordered Capt. Sam Means to strip the surrounding countryside of horses suitable for military use, to prevent their capture by the Rebels. In compliance, the Rangers marched to Tenleytown, outside Washington, and began working their way north through Montgomery County. They spared farmers with just one animal but otherwise took horses without regard to their owners’ loyalty, issuing vouchers redeemable through the Quartermaster Department. While some citizens “at first refused to part with their stock,” showing them Halleck’s order silenced most complaints. Means’s command reached Harford County by early July and began collecting horses along the Maryland/Pennsylvania border.

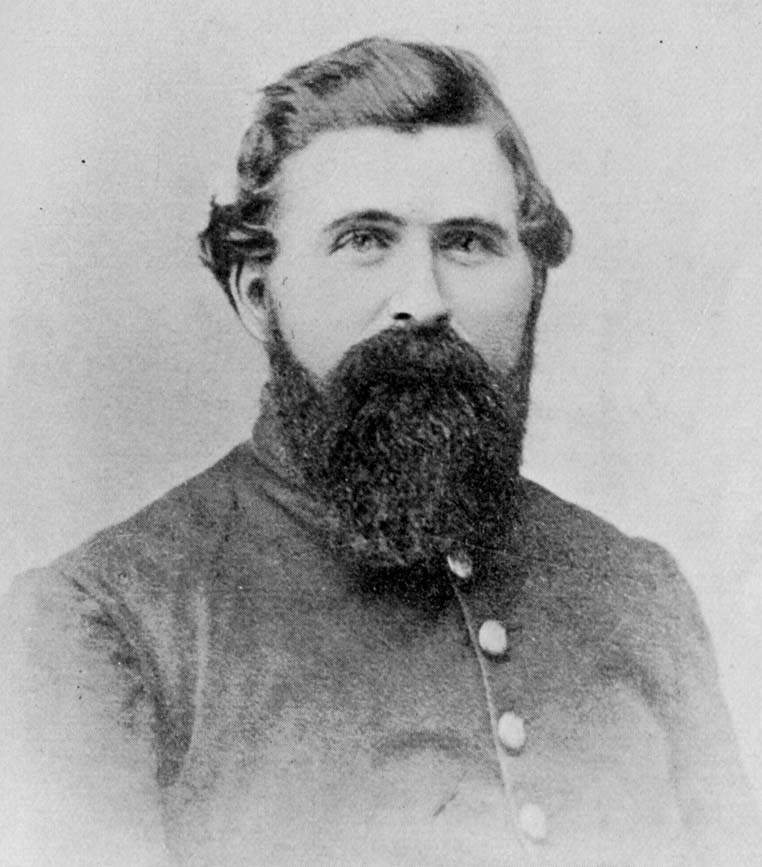

Samuel Carrington Means (August 5, 1827 – March 2, 1891), founder and first captain of the Independent Loudoun Rangers, a Union cavalry unit raised in Virginia in 1862.

The Rangers’ horse detail ended with the Confederate threat, and they returned to Point of Rocks on 15 July to await the arrival of Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s army on its way south from Gettysburg. Means set up camp at “Dripping Spring,” just north of town. The site was in a dense forest at the foot of the Catoctin Mountain. In short order the Virginians cleared out a shaded courtyard in front of their tents, which was used for morning roll call and as “a reception room for the company’s numerous lady visitors.” Not all, apparently, were ladies. Within a few weeks Sgt. Joe Divine, for one, found himself in the hospital in Frederick being dosed for syphilis. Still, Briscoe Goodhart declared the camp the best they would have during the war. Yet, even in this Eden, there were several serious fights. One pitted Sgt. William Bull and Cpl. Sam Tritapoe in a dispute over spilled coffee. As Goodhart explained, “the Rangers were fighting for principle, and as there was more or less principle involved in a cup of coffee, there was no reason why they should not fight for that as well as to fight [the Rebs].”

On 27 July, while the command was at Dripping Spring, Thomas Fouch enlisted, and gained the distinction of being the youngest Ranger. Like other members of the Fouch family, he had worked on farms around Waterford and Goresville but found himself all alone after his father Temple and brother Henry joined Means’s company in the summer of 1862. Fouch’s father claimed his 5-foot, 4-inch son was 17 and was joining to avoid Confederate conscription. Tom was, in fact, barely 15 (a postwar medical report put his age at enlistment as just 13 years and 4 months).

***

Meade wasted far less time getting the Army of the Potomac on the move than McClellan had after Antietam, although he retraced roughly the same route south through Loudoun County. After assembling his forces at Berlin and Sandy Hook, the Union commander sent the 5th Corps across the river on pontoon bridges to occupy Lovettsville on 17 July. At the same time, Kilpatrick’s cavalry division scouted ahead to Purcellville and Waterford. The next day a tide of blue engulfed north Loudoun, as Meade established his headquarters in Lovettsville and the 1st Corps crossed at Berlin and marched into Waterford that same morning. To the west, the 2nd and 3rd Corps crossed at Harpers Ferry and camped near Hillsboro, while the 5th Corps advanced from Lovettsville to Wheatland. These masses of men pushed farther south a day later to bivouac at Hamilton, Purcellville, and Woodgrove, and were followed by the 11th Corps, which camped south of Waterford, and the 12th Corps, which skirted the base of the Blue Ridge. Racing to beat Lee to Culpeper, Meade’s entire army passed beyond Loudoun’s southern border by 23 July.

View of Loudoun across the Potomac from Berlin. Double pontoon bridges speeded the crossing of Meade’s army into Virginia (October 1862 photograph by Alexander Gardner, Library of Congress).

While the vast army’s transit of Loudoun was fleeting, it was memorable. The 1st Corps began pouring into Waterford at 10 A.M. on 18 July and, with their departure and the simultaneous arrival of the 11th Corps the following day, the village was awash in blue. Rebecca Williams counted 600 wagons in the supply train, and, watching all the infantry and artillery regiments pass, she assumed, incorrectly, that it must be the greater part of Meade’s army. The 1st Corps set up its camps close to the village, with a large body along Catoctin Creek and others on Amasa Hough’s farm at the northwest end of town. As they had twice done the year before, residents turned out to welcome their Union heroes and feed, or at least give water to, as many as they could. The 7th Indiana Infantry had fond memories of their brief stay.

This part of Loudoun County had a preponderating Quaker population, among whom … we found Friends indeed. On nearing the outskirts of [Waterford] our advance was met by a party of citizens who on learning the purpose to go into camp soon one of them, pointing to a large bluegrass pasture nearby said “There’s grass for thy horses, a fine spring for thy men and beasts, and ricks of cordwood for thy cooking.” The invitation was accepted, gratefully, and it needs not the telling that no order touching top rails was necessary during our stay there.

Sunday afternoon, 20th[sic, 19th] again on the march. It was oppressively hot; as we passed through the village the street was lined with citizens–men in broad-brimmed hats and drab coats, women dressed in the modest garb of their sect, and young ladies and misses slightly more fashionably habited than their mothers–all extending to us their fare-thee-well. Here and there, close by the roadside, was a group of three or four to a half-dozen of these demure young Quakeresses–all sisters, one would judge from their appearance–astonishing the number of thirsty men in the line; to be honest, even I must plead guilty. [In a footnote the author acknowledged that one of the girls encountered that day, Lizzie Dutton, later married a member of his regiment and was, at the time of his writing, secretary of their veterans’ association.]

It had been noticed that among our many visitors there were but few youngish men. Inquiries as to why this was brought the answer, “Many of them are in a Maryland Union regiment.” How do you reconcile that with your religious faith? was asked of one. “We do not call this war, but correcting wayward children.”

21st: [sic, 20th] lay all day near a miserable Secesh town named Hamilton, in the same county, and the day following moved to Middleburg….”

While no one else met his future bride that day, others had equally pleasant memories. A member of the 39th Massachusetts Infantry called Waterford “a right smart place” with about 600 mostly Union inhabitants. American flags waved from some of the houses and women stood in front of their homes offering water to the troops. The New Englander had heard that “several hundred [sic] Union soldiers had enlisted there” and noted, “They do not take Reb. Scrip.”

A soldier in the 84th New York Infantry was similarly impressed.

[After] passing through Maryland and across the Potomac [we came] through the greatest little Union town of all we had seen yet. Nearly at every house, on the porch or stoop, and on the sidewalks, were the beautiful ladies, passing water, and bestowing their real cheering words and blessing, for the soldier-boys, smiling such sweet smiles, which none but real Union ladies know how to smile. Flags and white handkerchiefs were waving at nearly every house–such is the picture of the Union town of Waterford, Va.

Many passing through the village that weekend were struck by the profusion of Union flags. One banner had been hastily sewn by the three young Matthews sisters, Annie, Edie, and Marie, almost certainly for this occasion. Its 35 stars suggest it was made shortly after West Virginia became a state in June, and their concentric arrangement in the “Baltimore pattern” reflects the family’s ties to that city. Although the flag would later be proudly displayed whenever Union troops passed by the family farm, Clifton, the girls would have been in town that day, probably at the home of their aunt, Maggie Gover. At other times, the “treasonous banner” had to be hidden under a floorboard in their attic, where it survived several searches by Southern soldiers.

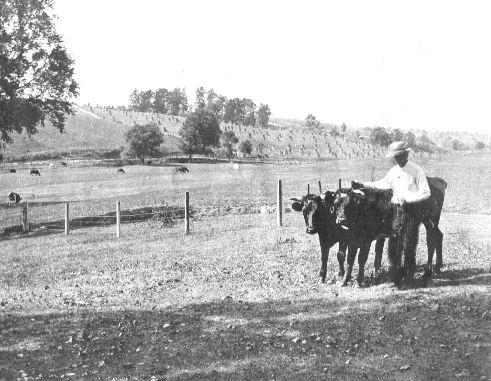

Clifton, home of Annie, Edie, and Marie Matthews, circa 1860.

The Loudoun Rangers accompanied the 1st Corps to Waterford and remained there for several days. Briscoe Goodhart quoted an account of a grand ball staged by officers of the 24th Michigan Infantry in the town’s honor.

Waterford, a most beautifully embowered and intensely loyal village. It seemed strange to find so patriotic a place in the Confederate dominions. That evening the merry maidens of the place with elastic step tripped the fantastic toe with our army officers. The streets were lined with smiles and beauty. Windows and balconies were filled with matrons, maidens, and children, who waved handkerchiefs and the starry flag, and cheered on the Union troops with many a hurrah for the Union. God bless Waterford!

Elsewhere in the county interaction between citizen and soldier was less cordial, especially with memories of the carnage at Gettysburg still fresh in the Federals’ minds. Members of the 49th Pennsylvania crossed the Potomac on the morning of the 19th and camped on Robert Wright’s “plantation” at Wheatland. Having marched all day with no time to eat, the foot soldiers were angered to discover the former militia general had put a chain on his water pump. One foraging party got into a dispute with a nearby farmer who would not give them any food. (His stacks of grain were later set on fire.) At the next farm a soldier held a gun on the owner, while a second went under the house to retrieve geese, chickens and eggs. That night General Wright’s barn was deliberately torched. The soldiers later heard that the owner had “one of his negroes tied up for telling the Yankees who he was.”

Mrs. John Janney was appalled by the destruction of “the best built, and the finest barn in the county,” along with large stores of flour, a carriage and “superior” farming equipment. Alcinda’s mood grew even darker when she heard that the soldiers had taken everything Wright had “in the way for food,” leaving his neighbors to feed him and his family. “He is almost literally ruined. This done by the enlightened North, to the Southern savages. Oh! How hard it is, really, to forgive your enemies, but vengeance belongs to God. He will repay it.”

Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s 11th Corps passed through Waterford on 19 July and camped between that town and Hamilton. Howard took over Israel Warner’s home for his headquarters, and while he treated the owner with respect, there were problems. When soldiers broke into Warner’s corcrib, he persuaded the general to station guards there to see that the corn was measured before being taken away. Yet even though the farmer got an accurate voucher for the grain, he was never paid for his loss. Two horses also disappeared, but the corps quartermaster refused to issue a voucher for “stolen property.” Howard’s men also camped on the nearby farm of Bushrod Fox., where two horses, wheat and hay were taken.

Farm products like these oxen at Clifton and the haystacks in the distance are examples of some of the resources commandeered or destroyed by Union soldiers passing through Loudoun in July 1863.

Such losses were the norm throughout the county. On 22 July, two and a half miles west of Hillsboro, tenant farmer George Virts found himself hosting members of Gen. John Geary’s command, then part of the 12th Corps, which camped at the farm he rented from the Thompson family. His loyalty to the Union proved no safeguard against losses. The soldiers took nearly all of his livestock and poultry, along with tools, harness, the food out of the kitchen and pantry, and even blankets off the beds and a keg of vinegar stored in the cellar. When Virts complained to Geary that night, the general told him to come back the next morning, but the entire command headed south before the matter was resolved.

Evidence suggests that Halleck’s earlier order to impress horses in Maryland was used to justify similar action in Loudoun. Nettie Dawson wrote that Meade’s army was “taking all the horses, but few they will find with southerners. Wheat is all taken to feed to the horses.” The wheat had just been harvested, and in many cases what the Federals did not use they burned. Whatever their loyalties, farmers throughout Loudoun breathed easier after the immense swarm of blue locusts passed.

Read more about how the Civil War impacted northern Loudoun County in Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia by Taylor M. Chamberlin and John M. Souders, available online here.