One of the joys of summer is enjoying a cold drink on a hot day. Before electricity and modern refrigeration, Waterford residents, like those in other rural American villages, had to rely on naturally produced ice harvested in the winter and carefully stored to last into the warmer months. In this excerpt from When Waterford and I Were Young, author John Divine explains Waterford’s ice houses, several of which still remain today, although not in use!

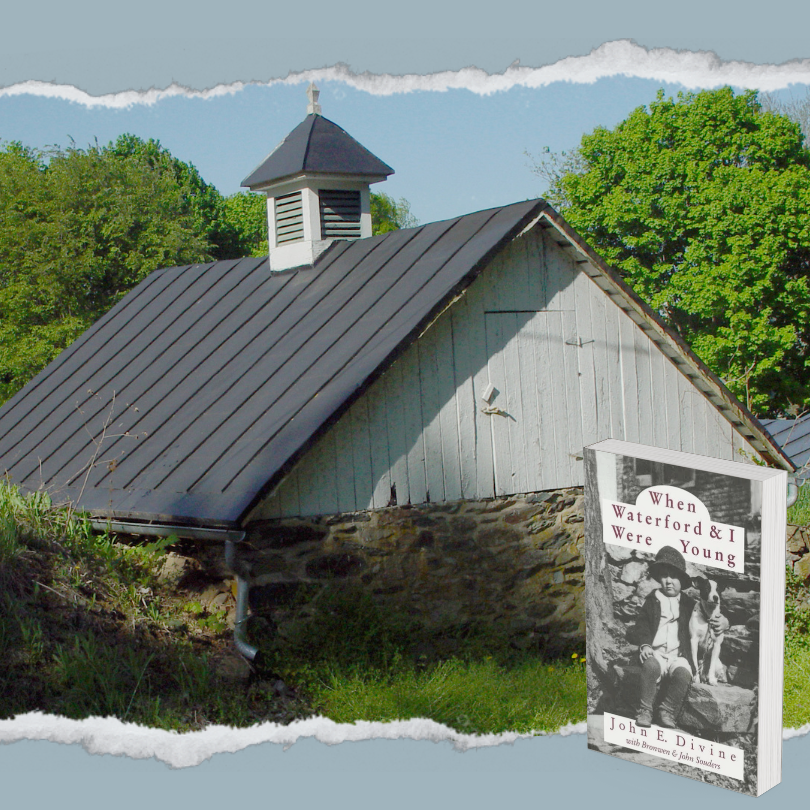

Before modern refrigeration came to Waterford, residents in and around the village relied on spring houses and ice houses to keep food and drink cool during the warm months of the year. Spring houses were not common in the town itself, as there were only a few reliable springs to work with, but many families had an ice house. I can remember at least a couple of dozen, although only a few remain today. One of the best is on the south side of Patrick Street, a well-built stone chamber about 12 feet square and as many feet below ground. A weatherboard shed above keeps the elements out.

Cutting and hauling ice to stock these structures was a regular winter chore. In a hard winter any still body of water would freeze thick enough to provide good blocks of ice. If a broad, slow-moving creek or mill pond was not at hand, some farmers would maintain a small pond just for the purpose.

When the ice was several inches thick and ready to harvest, it would be cut into manageable blocks with special coarse-toothed saws. My father [Jacob Elbert “Eb” Divine (1874-1966)], by the way, invented a set of giant tongs to drag the blocks from the water. The tongs were hitched to the horse traces, and the harder the animal pulled on a chunk, the tighter the device clamped. The blocks were then hauled to the ice houses and laid down with a good layer of straw or sawdust all around as insulation. Emma Myers still recalls cold lemonade in the summer-delicious despite the bits of wet sawdust embedded in the ice.

In warmer parts closer to the coast large quantities of ice were routinely brought in by ship from New England and other points north. Most years, though, Waterford had no shortage of winter to produce all the ice it wanted.

A local farmer recorded with obvious feeling one spell of such zero- degree weather in December 1867: “Cold all day. Very cold but thank goodness the wind has stopped blowing…Too cold to think of doing anything. Almost froze by the fire.”

That was not just a figure of speech. On Christmas day in 1848 Mary Reed wandered away from her house south of the village and disappeared. Her neighbors searched high and low, but it was three weeks before David Birdsall came across her frozen body on Mrs. Thurza Rice’s place.

January 1912 must hold the local record for bitter cold. At Clifton, an old farm just south of town, Leroy Chamberlin’s wife Charlton noted in her diary on the 6th that things were freezing in the house and cellar, despite the wood stoves. On the 9th a high wind brought in still colder temperatures, accompanied on the 12th by heavy snow. By the evening of the 13th, the thermometer read 14 degrees below zero, and even heavy covering could not keep the apples in the cellar from freezing. The next morning the mercury stood at minus 25! ” Went to the barns at 5:30 A.M…horses literally covered with frost. Decidedly the coldest weather that has been known here. 30 below in Waterford….”

The struggle with January continued. On the 16th, ” Very high wind all night and today. Snow drafting badly. Tried to go to milk train [at Paeonian Springs] in morning. Could get only halfway-road completely closed. All the streams frozen, had to cut holes in branch for stock to drink…all stock suffering from cold. 17th…went with horses to help open roads. Three teams and about 15 men out. Assisted in cutting through about a half mile drift…reached Paeonian at noon. Brought back empty [milk] cans.” There is a lot to be said for central heat, insulation and snow plows.

It was another modern convenience, electricity, that eventually ended the era of the ice house-and changed a lot more besides. Service finally reached Waterford in the 1920s, provided by old Leesburg Power, and one by one families wired their houses.

One of the biggest changes was in lighting. To a village long used to making candles or trimming the wicks and cleaning the sooty chimneys of coal oil lamps, the workings of electricity, and even the new vocabulary, took some getting use to. In one family, the elderly maid, on encountering her first electric lamp, tried to extinguish the light by blowing on the bulb. A more forward-thinking resident couldn’t wait to “get the church electrocuted.”

Find this and other anecdotes from Waterford’s past in When Waterford and I Were Young by John E. Divine with Bronwen and John Sounders, 1997