General History of Waterford, VA

By Debbie Robison

Waterford is a special place. Much of the historic village reflects the various time periods in which it was built, from a mill race dug in the 18th-century colonial period, to log homes, craftsman shops, and dry goods stores constructed at the start of a new nation, to new businesses begun in the Victorian era, and onward to buildings restored in the 20th-century colonial-revival period. In Waterford, it feels like history.

The story of Waterford can be told hand-in-hand with the story of America. The impact of religious revivals, manufacturing innovations, slavery, economic depressions, and laws that governed free Black people all touched this village. The individual histories of each home, shop, barn, and outbuilding, as well as the people who lived here, are all part of a larger story. And that is, in part, what makes Waterford so special.

The village was founded ca. 1784 by Joseph Janney, a Quaker businessman formerly from Pennsylvania, who offered lots for sale and lease near a water-powered grist mill and sawmill.[i] The land where the village was built was originally settled by Quakers, members of the Society of Friends, when John Mead purchased 703 acres in 1733.[ii] This was during the time of the Great Awakening, a religious revival in the 1730s and 1740s that led to an increase in religious conviction. Other Quakers soon followed Mead and settled in the area where they found religious tolerance as well as fertile, well-watered soil. They farmed tobacco, raised families, and established a Quaker meeting.[iii] During colonial rule, tobacco was shipped to Great Britain, who regulated and restricted trade. Once the flour trade opened to the British West Indies, grist mills were established along streams throughout the area, including the mill built by Mahlon Janney on Kittocton (now Catoctin) Creek ca. 1762.[iv]

The village began with a dry goods store, saddlery, cabinet shop, tannery, and blacksmith shop.[v] The store did not prosper since farmers and millers, who were store patrons, struggled to find international buyers for their goods after the Revolutionary War. This was because, at the start of the new nation, America was only a confederation of states without a federal constitution to provide collective bargaining power for international trade agreements. Despite this hurdle, the other businesses succeeded, with young apprentices providing much of the labor while learning valuable skills.[vi] In time, former apprentices and employees of these first manufacturing enterprises started their own businesses and purchased lots, along with others, in the expanding village.[vii]

The American Revolution heightened the ideals of religious liberty and freedom, which sparked the Virginia General Assembly to enact a law in 1782 allowing any person to emancipate his slaves.[viii] During this Second Great Awakening, a number of local Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists freed their slaves, joining the Quakers who had disavowed slavery prior to the war.[ix] Free Black people settled in the area, possibly attracted by job opportunities and a willingness of the Quaker population to assist them, establish store accounts, and sell them lots.[x] Some of the non-Quaker proprietors, particularly the tavern keepers, had enslaved Black people work in their establishments.[xi]

Pre-Civil War education in Waterford varied depending on if you were a White person, free Black person, or an enslaved person. Early on, some free Black children learned to read and write as part of their apprentice agreement.[xii] In 1819, Virginia outlawed allowing enslaved people to meet at schools to learn to read and write, and then made educating free Black people illegal in 1831 in response to increased abolitionism in the north.[xiii] The Quakers in town were devoted to education and had built a schoolhouse in 1805 on the meeting house grounds.[xiv] In 1818, Virginia created a literary fund to pay for the education of poor students.[xv] The fund helped pay for teachers in Waterford as early as 1818 when William Adams of Waterford was teaching.[xvi] In 1822, three Waterford residents were paid for teaching: Jacob Mendenhall, who operated an academy in Waterford, Robert Braden, Jr., and Ann Ball.[xvii]

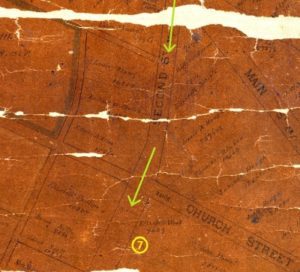

In 1801, the village officially became a town with the ability to lay off land into lots and streets. [xviii] This enabled the town to expand beyond the existing Main Street up, what in the early days was called, Federal Hill.[xix] The town continued to grow and fill with tradesmen, tavern keepers, and craftsmen who made furniture, hats, shoes, saddles, and clothing. The building trade was so busy that a second water-powered sawmill was built off Balls Run to churn out even more lumber for the housing boom.[xx] Most of the new houses were constructed of brick, likely made at the brick manufactory that was established in a meadow by the mill race.[xxi]

The pace of building slowed to a crawl after Thomas Jefferson enacted the Embargo of 1807 that prevented merchant ships from trading in foreign ports. This resulted in an economic depression and the financial ruin of the Waterford grist mill, which relied on foreign trade.[xxii] Building in town resurged once the embargo was lifted in 1809.[xxiii]

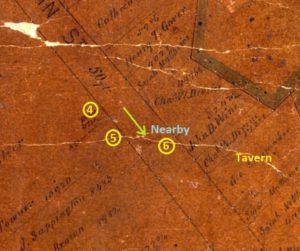

Spurred by new innovations in America’s first Industrial Revolution, a woolen factory was established at the south end of town.[xxiv] This corner of Waterford would come to be a manufacturing hub where blacksmiths, carriage makers, wheelwrights, and machinists worked at their anvils. Down the street, the nearby sawmill operation added machinery for a plaster mill and clover mill to foster increased local agricultural yields.[xxv]

After the War of 1812, the town greatly expanded around new streets and alleys laid out in a grid pattern during America’s 1815-1819 economic speculative boom. To support the growth, a bank was established briefly in Waterford before the state required it to close.[xxvi] Brick dwellings were constructed in the “New Addition,” the grist mill was replaced with a larger three-story brick mill, and a commodious three-story brick house with a lower-level store was built in the center of town – – right before everything came to a halt with the 1819 banking panic and years-long depression. The proprietors of the Waterford Mill and the large stone tavern were forced to sell their businesses to meet their financial obligations.[xxvii] The long economic recovery, recession, and depression that followed stalled most growth in the town, though industrial manufacturing of agricultural implements continued to evolve.[xxviii]

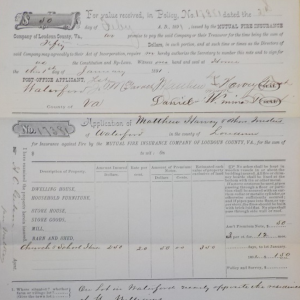

A period of American business expansion from 1844-1856 included the establishment of a fire insurance company and construction of a few more houses and the Baptist Church edifice in Waterford.[xxix] A fraternal benevolent association, Evergreen Lodge No 51 of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, was organized in 1847. They purchased a three-story brick house on Main Street where they held meetings and transacted business.[xxx]

But soon the Civil War commenced. Men from Waterford and other strongly Unionist areas of north Loudoun formed the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers, a federal cavalry company under the leadership of local miller Samuel C. Means.[xxxi] At least one free Black man from Waterford joined the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, while a few more served in other Union units, sometimes informally. A handful of White residents voted for secession, though, and several fought for the Confederacy.[xxxii] The town was beset by raids, including a bloody skirmish at the Baptist Church, and intermittent occupation by Confederate troops.[xxxiii] Post-war reconstruction benefited the Black population when they constructed a school for their children, aided by the federal Freedman’s Bureau and a Philadelphia Quaker society.[xxxiv]

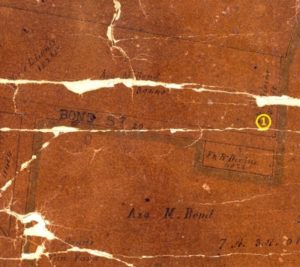

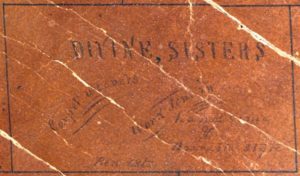

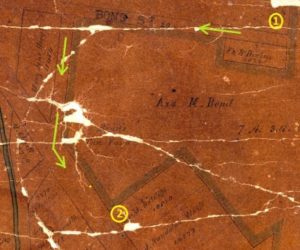

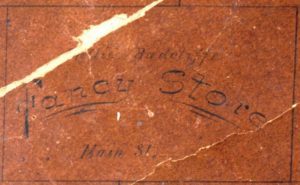

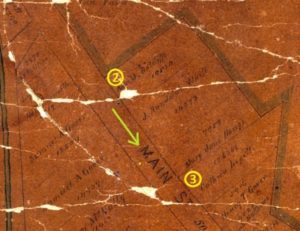

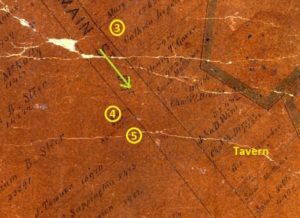

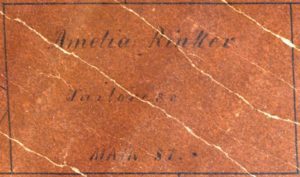

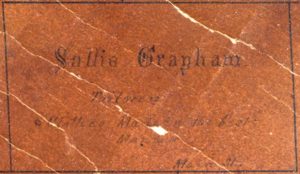

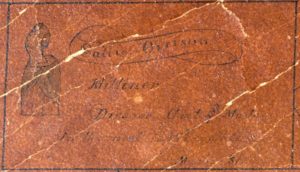

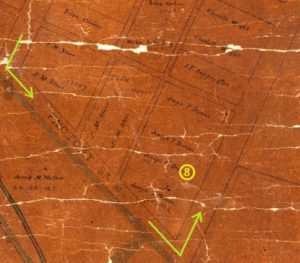

Little growth followed until, bit-by-bit, Waterford started to shake off its stagnant economy. In 1867, passenger railroad service from Alexandria arrived at nearby Clarke’s Gap station, and two years later, a daily stage line ran between Waterford and the depot.[xxxv] This benefited Waterford homeowners who earned additional funds by boarding urban-area residents in the summer months.[xxxvi] In 1875, the town of Waterford was reincorporated and a map of the town was created that advertised businesses, including a number of women-owned establishments.[xxxvii] The new charter allowed the town to collect a town tax, make public improvements, and have use of the county jail.[xxxviii]

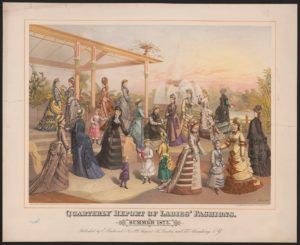

By the time industries fueled America’s business expansion from 1879-1893, Waterford carpenters were already quite busy. New types of specialty stores, such as grocery stores, drug stores, and tin shops opened; several in new buildings. And several Victorian-style homes were constructed on available town lots to house the shopkeepers and clerks.[xxxix]

This period of growth coincided with the Third Great Awakening. Increases in church attendance resulted in the return of a Presbyterian congregation to Waterford and construction of a Methodist church edifice for White congregants on the hill and for Black congregants near the mill.[xl] The temperance movement, which sought to limit and then ban the consumption of alcoholic beverages, found new life in Waterford. Advocates met in the Temperance Hall above the Chair Factory.[xli] Other community activities at the time included attendance at literary society meetings held in local homes.[xlii]

Waterford saw remarkable changes during the Second Industrial Revolution. In 1884 you could place a telephone call at Dr. Connell’s store in Waterford to Clarke’s Gap after lines were run between the two places.[xliii] Or you could receive electric therapy treatment from Dr. Connell with the use of his Electric Battery apparatus.[xliv] Mr. J. F. Dodd improved the Waterford Mill by putting in machinery for making roller process flour.[xlv] And in 1914, E. H. Beans, Waterford’s enterprising liveryman, acquired an automobile.[xlvi] The type of employment available in Waterford also changed. By 1910, there were no longer any Waterford craftsmen making chairs, furniture, saddles, or shoes, which by then were made in urban factories. However, there was a stenographer, electrician, and a “phone girl” working in the Central office.[xlvii]

The Industrial Revolution led to an increase in the pace of urbanization. The population of cities swelled as employment opportunities in factories and department stores rapidly grew. Farmers began converting fields into dairy farms to supply milk to local creameries that made butter for the burgeoning Washington, D. C. market. Kingsley Creamery built a creamery on the Waterford town lot in 1885, but its’ duration was short lived.[xlviii] Local creameries were made obsolete by new inventions that allowed city factories to obtain cream directly from farmers.[xlix] Local water-powered grist mills were also declining. Engineering advances in mill technology enabled large flour factories to be built on more substantial and reliable waterways.[l]

In consequence of urbanization and changes in manufacturing, both White and Black residents of Waterford moved to cities, notably Washington D.C.[li] When they left, many of the older structures on Main Street were purchased by Black families, greatly increasing home ownership for Waterford’s Black residents.[lii]

During the Great Depression, buildings were purchased by wealthy preservationists who wanted to revive Waterford into a “Little Williamsburg.”[liii] Colonial-revival fever struck Waterford. Buildings were stabilized, altered, and “restored” with hand-hewn beams and colonial-style door hardware. The Waterford Foundation, an early preservation organization, was formed in 1943 to encourage interest in restoring the town to an earlier period.[liv] Fundraising fairs featured early crafts made by local artisans and home tours. The village and tour buildings were provided with histories, often with dates erring on the side of the colonial period, never mind that Waterford was founded after the American Revolutionary War.[lv]

In time, White families began moving to Waterford in search of post-World War II housing, while the Black population dwindled as the younger generation sought opportunities elsewhere.[lvi]

The national historic preservation movement took hold after the enactment of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966 that established funding and guidelines for preservation programs.[lvii] Waterford was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1970. A number of Waterford’s historic structures were placed under easements with the state in the 1970s to ensure appropriate preservation treatment.[lviii]

The Waterford Foundation continues its work to preserve historic properties owned by the Foundation and to further the understanding of the history of the village in support of its education mission.

[i] Thomas Hague to Joseph Janney, Loudoun County Deed Book O:9, Lease and Release, May 1, 1781; also U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935, Pennsylvania, Montgomery, Abington Monthly Meeting, Men’s Minutes, 1756-1765, as viewed at ancestry.com, also Deed from Joseph Janney to Richard Richardson, Loudoun County Deed Book P:338, June 12, 1785; also, Deed from Joseph Janney to Joseph Pierpoint, Loudoun County Deed Book P:340, June 12, 1785; also Deed from Joseph Janney, Merchant of the county of Fairfax, to Thomas Moore Junr of Loudoun County, Loudoun County Deed Book O:158, August 17, 1784. Alexandria was then part of Fairfax County.

[ii] Deed from Catesby Cocke to John Mead, Prince William County Deed Book B:186, November 20, 1733, as viewed at https://www4.pwcva.gov/Web/user/disclaimer

[iii] Deed from John Mead to Amos Janney, Prince William County Deed Book Index C:400; also Deed from John Mead to Francis Hague, Fairfax County Deed Book A1:282, March 19, 1743.

[iv] Deed from Francis Hague to Mahlon Janney, Loudoun County Deed Book C:367, June 14, 1762, mentions mill features; Joseph Janney and Mahlon Janney were second cousins.

[v] Index of Indentures & Bound out Children Papers, Loudoun County Clerk of the Circuit Court Historic Records, as viewed at Indentures.pdf (loudoun.gov)

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Levi James was apprenticed to Asa Moore to learn the trade of saddler in 1791. He purchased a lot on main street, Loudoun County Deed Book 2W:34, 1810; Henry Burkett, who lived with Thomas Moore Jr for three years, paid ground rent on a lot, and two people (Jesse James and Daniel Lovett) who had been apprentices of the Moore family live with him, Loudoun County Deed Book U:266; see also Index of Indentures & Bound out Children Papers, Loudoun County Clerk of the Circuit Court Historic Records, as viewed at Indentures.pdf (loudoun.gov)

[viii] “An at to authorize the manumission of slaves,” Henings Statutes, Volume XI, Chapter XXI, May 1782, p. 39-40, as viewed at https://vagenweb.org/hening/vol11-02.htm

[ix] Ancestry.com. U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Source material: Swarthmore, Quaker Meeting Records. Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, 1758. Examples of others who emancipated their enslaved people include Reverend Amos Thompson (Presbyterian), William Osburn (Baptist, Buried at Ketoctin Baptist Church Cemetery), John Littlejohn (Traveling Methodist preacher, Leesburg), Charles Binns (Methodist)

[x] John Williams Store Ledger 1805-1808, microfilm from Duke University, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia.

[xi] Federal Census of 1810, as viewed on ancestry.com

[xii] Nathaniel Minor Indenture, 1802, Bound Out Children and Indenture Papers, Catalog number I1801-0016-1384, Loudoun County Clerk of the Circuit Court Historic Records; Samuel Minor Indenture, 1802, Bound Out Children and Indenture Papers, Catalog number I1801-0017-1385, Loudoun County Clerk of the Circuit Court Historic Records; Peter Manley Indenture, 1799, Bound Out Children and Indenture Papers, Catalog number I1799-0037-1318, Loudoun County Clerk of the Circuit Court Historic Records, as viewed at https://lfportal.loudoun.gov/LFPortalInternet/0/edoc/326239/Indentures.pdf

[xiii] An act reducing into one, the several acts concerning Slaves, Free Negroes and Mulattoes (1819), Virginia Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia, Vol 1, Thomas Ritchie, publisher, Richmond Virginia, p. 424, as viewed at https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Revised_Code_of_the_Laws_of_Virginia/VVhRAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=virginia+revised+code+1819&printsec=frontcover ; Also, An Act to amend the act concerning slaves, free negroes, and mulattoes (1831), Acts Passed at the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Chapter XXXIX, p. 107, as viewed at https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/lu9QAQAAMAAJ?gbpv=1&bsq=Free%20Negroes

[xiv] Quaker Meeting Minutes, Fairfax Monthly Meeting, March 23, 1805, as viewed on ancestry.com

[xv]An Act appropriating part of the revenue of the Literary Fund, and for other purposes, Acts Passed at the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Feb. 21, 1818, Thomas Ritchie, publisher, Richmond, p. 14, as viewed at https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/kMo_AQAAMAAJ?gbpv=1&bsq=Literary%20fund

[xvi] Loudoun County Schools 1789-1910, School Commissioners and Treasurer Bonds, Box 1 of 2, Misc. Papers-Schools, School Commissioners, 1818-1819, Loudoun County Clerk of the Circuit Court Historic Records, Leesburg, Virginia.

[xvii] Loudoun County Schools 1789-1910, School Commissioners and Treasurer Bonds, Box 1 of 2, folders Schools 1820-1829, Loudoun County Clerk of the Circuit Court Historic Records, Leesburg, Virginia; Also, “Obituary. Noah Haines Swayne,” New York Tribune, June 10, 1884, p. 2, which notes that ex-Justice of the US Supreme Court Noah Swayne was sent to the academy of Jacob Mendenhall at Waterford, Virginia.

[xviii] “An Act to establish several towns,” The Statutes at Large of Virginia, January 8, 1801, as viewed at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.35112104867314&view=1up&seq=276

[xix] James Russell, “Houses for Sale,” Washingtonian, April 10, 1810, as viewed on geneologybank.com.

[xx] Mahlon Janney writ of adquoddamnum for dam for grist mill, Loudoun County Order Book W:241, July 11, 1803; Mahlon Janney Jr inherited the sawmill from his uncle, Mahlon Janney, Loudoun County Will Book K:119, June 8, 1812.

[xxi] Mahlon Janney deed to Edward Dorsey, Loudoun County Deed Book 2D:327, September 22, 1803; Nathaniel Manning deed to John B Stephens (mentions brick yard of James Russell), Loudoun County Deed Book 2U:32, May 13, 1816.

[xxii] Loudoun County Land Tax ledger 1807, 1809, microfilm, “Land Tax Records,” Reel 170 (1800-1815), Library of Virginia, Richmond.; Also, “A Merchant Mill for Sale,” The Washingtonian, April 2, 1811, p. 4.

[xxiii] Loudoun County Land Tax Ledger, 1810, microfilm, “Land Tax Records,” Reel 170 (1800-1815), Library of Virginia, Richmond.

[xxiv] Young men bound out to James Moore & Co (Woollen Manufactory), see Loudoun County Minute books of 1813 paged 6:235, 6:285, 6:344, and 7:105; see also James Moore & Co, “Domestic Cloths,” Daily National Intelligencer, October 15, 1814; Also, Loudoun County Will Book P:126, December 12, 1812.

[xxv] Noble S. Braden, “Clover Mill,” Genius of Liberty, July 18, 1829.

[xxvi] “Petition for charter for the encouragement of Agriculture and Domestic Manufactures,” Legislative Petitions, November 10, 1815, Library of Virginia. (Bank went into operation 10 Jun 1815.); Act required unchartered banks to close, Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia p 115, February 24, 1816.

[xxvii] Waterford Mill transferred to trustees for creditors of Braden, Morgan and Co., Loudoun County Land Tax Ledger, 1826, microfilm, “Land Tax Records,” Reel 172 (1824-1831A), Library of Virginia, Richmond.; “Sale under Deed of Trust,” Genius of Liberty, July 20, 1819.

[xxviii] James M. Steer, “Manufactory of Agricultural Implements.,” Genius of Liberty, Vol. 21, No. 42, October 21, 1837; William Addams, “New improved Wheat Fan.,” Genius of Liberty, March 18, 1817, p. 3.

[xxix] Loudoun County Land Tax, 1855, microfilm, “Land Tax Records,” Reel 487 (1853-1856), Library of Virginia, Richmond. John B. Dutton was assessed tax on one lot with a building value of $500 with a notation of “Buildings added.”; Also, Deed from Samuel C Means to Robert Thomas, Loudoun County Deed Book 5T:388, January, 26 1861; Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Loudoun County, “The Act of Incorporation, Constitution and By-laws of the Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Loudoun County, Va, W. Wooddy & Son, 1849.

[xxx] Evergreen Lodge No 5 William S Wood et. al. v. John Hough et. al. Loudoun County Chancery Case M1005, index number 1860-011, as viewed at https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=107-1860-011

[xxxi] Briscoe Goodhart, Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers, U. S. Vol. Cav. (Scouts) 1862-1865., Press of McGill & Wallace, 1896, as viewed on Google Books.

[xxxii] Soldiers and Sailors Database, National Park Service, as viewed at https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm; James Lewis grave marker, located in Waterford, Virginia, identifies his unit; Also, Albert O Brown grave marker, located in Waterford, has a military marker indicating Confederate States Army (CSA), Virginia 35th BN.

[xxxiii] John W. Geary, “Report of Col. John W. Geary, Twenty-eighth Pennsylvania Infantry, including operations of his command to May 6, 1862,” The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I-Vol V. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1881, p. 528, as viewed at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077730194&view=1up&seq=3&q1=waterford ; Chas P Stone, Correspondence to Maj. S. Williams, 28 Aug 1861, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I-Vol V. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1881, p. 582; Skirmish at Waterford, 27 Aug 1862, The War of the Rebellion: A compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Operations in N. VA, W. VA. And MD, Chap XXIV, p. 242 as viewed at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077728222&view=1up&seq=3&q1=waterford

[xxxiv] Letter from Smith to Col S. P. Lee, Freedmen’s Bureau Letters, M1048, Roll 5 p.219 #367, May 8, 1867; Letter O.S.B. Wall to Col. S. P. Lee, Freedmen’s Bureau Letters, Supt of Education, M1913, 45, 908, December 17, 1868, as viewed on Familysearch.com

[xxxv] Annual Report of the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad, 1867. Courtesy Paul McCray; Also, Brown, Albert O., “Daily Stage Line From Waterford to Clark’s Gap Depot,” The Washingtonian, June 4, 1869, Leesburg, VA, Waterford Foundation archives.

[xxxvi] “Waterford Waifs.,” The Loudoun Telephone, November 15, 1889, p. 3, microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA

[xxxvii] Map, Waterford, Loudoun County, Virginia, from Surveys by James S. Oden, 1875, Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Loudoun County Records, 1849-1954. Accession 41374. Business records collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[xxxviii] Acts and Joint Resolutions Passed by the General Assembly of the State of Virginia, at the Session of 1874-5. Richmond, R. F. Walker, Supt Public Printing, 1875, as viewed on Google books at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Acts_and_Joint_Resolutions_Passed_by_the/uhQSAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=1875+waterford+incorporation+virginia+general+assembly&pg=PA141&printsec=frontcover

[xxxix] Loudoun County Land Tax, 1888, microfilm, “Land Tax Records,” Reel 854 (1888), Library of Virginia, Richmond, A. M. Hough building value, 1900 Federal Census lists A M Hough as a Dry Goods Salesman; “Oscar James has purchased the old cabinet shop of Lewis Hough and is building a dwelling house,” The Loudoun Telephone, May 17, 1889. Deed from L. Kate Rickard to F. J. Beans, Loudoun County Deed Book 6Z:254, May 17, 1887.

[xl] “A New Church Edifice,” The Loudoun Telephone, August 18, 1882 (Presbyterian Church); “Letters from Loudoun,” Alexandria Gazette, March 8, 1884 (Methodist church on hill); Deed from Mary Jane Hough to James Lewis and other trustees of the Methodist Episcopal Church, Loudoun County Deed Book 7B:14, July 3, 1888 (Methodist church by mill)

[xli] Map, Waterford, Loudoun County, Virginia, from Surveys by James S. Oden, 1875, Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Loudoun County Records, 1849-1954. Accession 41374. Business records collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[xlii] The Loudoun Telephone, January 16, 1885, p. 3., microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA. The Literary Society in good order.

[xliii] “Telephone in Waterford,” The Loudoun Telephone, August 22, 1884, microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA

[xliv] “U. S. Examining Surgeon, Dr. G. E. Connell. Chronic Diseases and Troubles Peculiar to Women a Specialty,” The Loudoun Telephone, October 1, 1886; The Loudoun Telephone, March 2, 1883, microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia.

[xlv] The Loudoun Telephone, July 3, 1885, p. 3, microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia.

[xlvi] “Waterford Waifs,” Loudoun Mirror, June 26, 1914, p. 4, microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia.

[xlvii] 1910 Federal Census, as viewed on Ancestry.com

[xlviii] “Waterford Flashes,” The Loudoun Telephone, July 31, 1885, p. 3.; The Loudoun Telephone, March 9, 1888, p. 3.

[xlix] “The Cost of Milk has been Increased: Consolidations,” Mathews Journal, Volume 4, Number 12, February 28, 1907, as viewed at https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=MJ19070228.1.1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——–

[l] “Old Grist Mills,” Page Courier, Vol 43, Number 52, March 31 1910, as viewed at https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=PCO19100331.1.1&srpos=1&e=——191-en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22old+grist+mills%22——-# ; Also, J. F. Dodd accepted a position with the Laurel (Md.) Roller Mill Co., to take charge and manage the large, handsome mill which they are building at that place. The Loudoun Telephone, October 11, 1889, microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia.

[li] “Waterford Waifs.,” The Loudoun Telephone, January 3, 1890, p. 3; “Waterford Waifs,” Loudoun Mirror, September 26, 1913, p.8; Also, S.A. Gover, “Store Room For Rent in Waterford,” The Loudoun Telephone, September 5, 1890, p. 3, microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia; Also, Loudoun County Deed Book 9D:467, March 12, 1918, A. E. Johnson, formerly A. E. Love, sold lot on main street when living in Washington D. C.

[lii] Deed to John Lee and Thomas Lee, Loudoun County Deed Book 7I:420, September 24, 1894; Deed to Alfonzo Palmer, Loudoun County Deed Book 8F:191, October 8, 1906; Deed to Philip P. Curtis, Loudoun County Deed Book 7T:330.

[liii] Solange Strong, “Waterford Wakens,” The Magazine Antiques, October 1949, p.280.

[liv] Waterford Foundation, Inc. Waterford (Allen B. McDaniel, pres.): to recreate the town of Waterford as it existed in previous times. The Commonwealth: The Magazine of Virginia, Volume 11, Virginia State Chamber of Commerce, 1944, p. 29.; Also, Waterford Foundation’s Twenty-Third Annual Homes Tour and Crafts Exhibit, 1966, p. 2.

[lv] Waterford Foundation Inc., Exhibit of the work of the artists and craftsmen of Loudoun County, Virginia, 1946.

[lvi] Often, the heirs of long-time Black residents sold the lots, for example: Loudoun County Deed Book 417:80, September 10, 1962; Loudoun Deed Book 1448:20, May 31, 1966; Loudoun Deed Book 350:533, November 7, 1955.

[lvii] U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, “Federal Historic Preservation Laws,” Washington, D.C. 1993 p. 6.

[lviii] Loudoun Deed Book 624:573, July 31, 1975; Loudoun County Deed Book 630:663, October 31, 1975; Loudoun County Deed Book 631:586, December 3, 1975.