Written by Robert Dabney Trussell. This article first appeared in the 50th Annual Waterford Homes Tour and Crafts Exhibit Booklet, October 1-3, 1993.

The American Civil War–it has been described variously as the war between the states; the conflict that pitted brother against brother; the battle for freedom or slavery.

It was a war of extreme points of view where the middle ground of rationality was razor thin or lost in the bloodletting. It was a war of opposing armies marching, foraging, camping and fighting over the rolling fields and idyllic towns of a new republic. The war involved every community in some way and likewise touched every citizen in the nation.

While most Americans both North and South marched to the cadences of their causes, Quakers in both regions struggled to heed their consciences. For the most part, members of the Society of Friends believed that both governments were wrong to use violence to settle their differences. Quakers opposed slavery as the vilest form of human degradation, superseded only by the act of killing.

Friends generally stood against a war that most Americans, religious denominations and political organizations of the time regarded as a righteous war. How could Quakers take such a stand?

The simplest reason stemmed from a primary precept of the Quaker faith that the light of God burns within every man, woman and child. Therefore, the sacredness of life was not to be violated in any manner. This moral stance had a secular human rights component that faulted both the Union and the Confederate governments. Friends found the federal government’s brutal policy toward Native Americans to be as inhuman as the South’s institution of slavery. Also, Quakers openly decried the North’s abolitionist propaganda while its manufacturers profited greatly from raw goods derived from slave labor.

At the same time, the Civil War altered the traditional isolationism of the Friends and thrust many Quakers into the turmoil of the time.

Even before the war, some Quakers risked their lives as participants of the “Underground Railroad” which provided a route to freedom for thousands of slaves. Quakers, even in the South, attacked slavery through newspaper articles, tracts, and nationally published Quaker journals. When hostilities did break out in 1861, numerous Quakers struggled greatly with their consciences, left their meetings for worship and took up arms against the Confederacy.

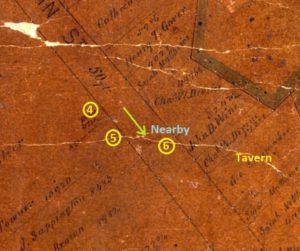

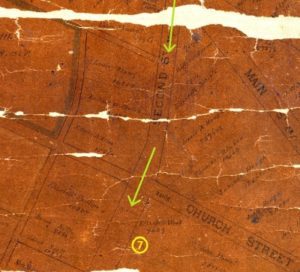

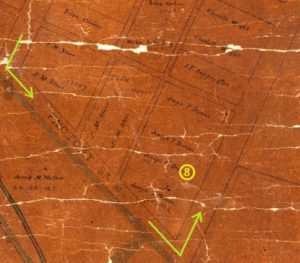

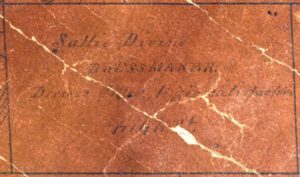

Quakers in the South and thereby in Loudoun County, found themselves at particular risk. This population of Friends was sizable, influential and prosperous. Following the land migrations of the 17th and 18th Centuries, Quakers settled throughout Virginia. More than 60 meeting houses were built in the Commonwealth and several Quaker communities were well established in Loudoun County. The town of Waterford became a major center for Quaker education and commerce, as well as the location of the Fairfax meeting.

This whole community of Friends was threatened by the war. Whereas Quaker pacifism was protected in the North (Abraham Lincoln’s great-grandfather was a Pennsylvania Quaker), being a Quaker in the wartime South was a liability.

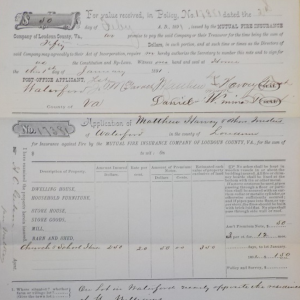

Quaker men who refused to enlist or answer the draft were frequently imprisoned and ridiculed. One Waterford Quaker objector was even abducted from his home, forced to march with an infantry unit and cruelly placed without defense in the front line of an attack during a battle. Somehow he survived that ordeal only to die from disease in a Confederate prison. The Fairfax Friends’ opposition to slavery left them vulnerable to discrimination or at least shunned by fellow Southerners. Rebel armies would target Quaker farms in the area for food and shelter. Farmers and merchants suffered great loss of property and business. Also the war cut off Quakers from their friends and relatives in the North.

Through it all, Friends in Loudoun County kept their faith and traditions alive and struggled to follow Christ’s words “to do unto others”. A poignant example of this belief is found in a letter written in 1863 by Susan Walker, a Waterford Quaker.

Susan Walker described an event that occurred early in the war. On Sunday, Friends of the Fairfax meeting arrived for worship to discover a company of Confederate regulars billeted in the stone meeting house. Both the house and the yard were strewn with stacks of rifles, flags and campaign gear. Soldiers relaxed on the meeting house benches and slept up in the gallery. As the Quakers entered, some soldiers rose to meet them with jokes about their plain attire and taunts about their anti-slavery beliefs.

But the Quakers were resolved to worship that day; a quick compromise was reached with the commanding officer. A portion of the meeting room was partitioned off with tenting allowing the Quakers a place to quietly wait upon God. The Quakers then invited the soldiers to worship with them. Curious about “how Quakers prayed”, several of the company joined them. During the silence, an elderly woman, moved by God’s presence, stood and spoke to the odd assembly. In a strong voice she prayed “God bless all here and that the wings of peace might return to our prosperous country and peace be with the strangers in our midst”.

With this the woman sat. So moved by her words, the soldiers wept openly: “…great tears coursed each other down their sun-burned cheeks”, wrote Susan Walker.

The year was 1861. Four long and bloody years of the Civil War still remained before peace finally returned to the Quakers of Waterford and the Nation.

Contributor: Robert Dabney Trussell who attends Goose Creek meeting in Loudoun County. Mr. Trussell lives in Rosemont, Maryland and works for the AFL-CIO in Washington, D.C.